“It should not be called landscape architecture because you are not making pictures, you’re treating the land as though it were a great conversation, as though you’re taking a piece out of the whole, as though you really appreciate the nature of things. Land isn’t just a hunk of real estate. Even a little square inch of it has many worms. Something’s going on. You can go as microscopic as you like.” Kahn, Lecture at Drexel University Architectural Society, 1968

Harriet Pattison (1928–2023), the Korman project’s landscape architect, collaborated closely with Kahn during the last decade of his life. Her influence is most evident in the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas, which opened in 1972. “Like most of [Kahn’s] landscape work and site-planning work in the ‘60s and ‘70s,” write Kahn scholars David Brownlee and David De Long, “this carefully articulated procession through a landscape was created in consultation with Harriet Pattison, who delighted in making calculated juxtapositions of environmental effects.” 1Louis I. Kahn: In the Realm of Architecture, condensed ed., introduction by Vincent Scully (Los Angeles: Universe, 1997) p, 223.

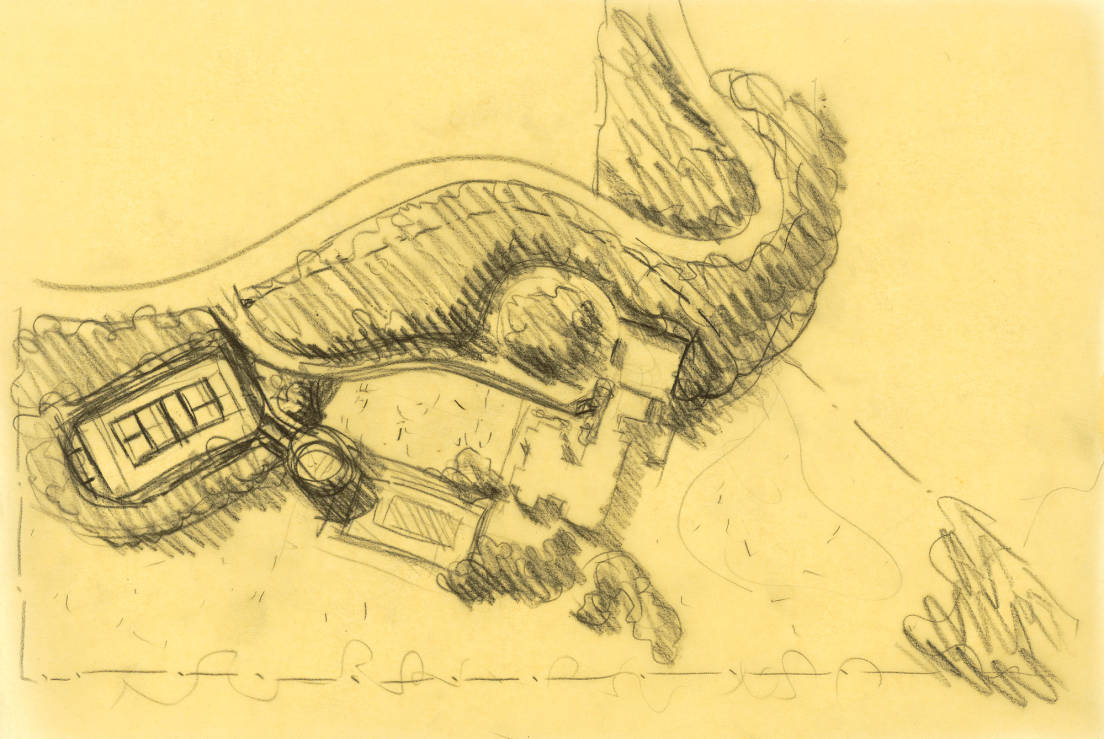

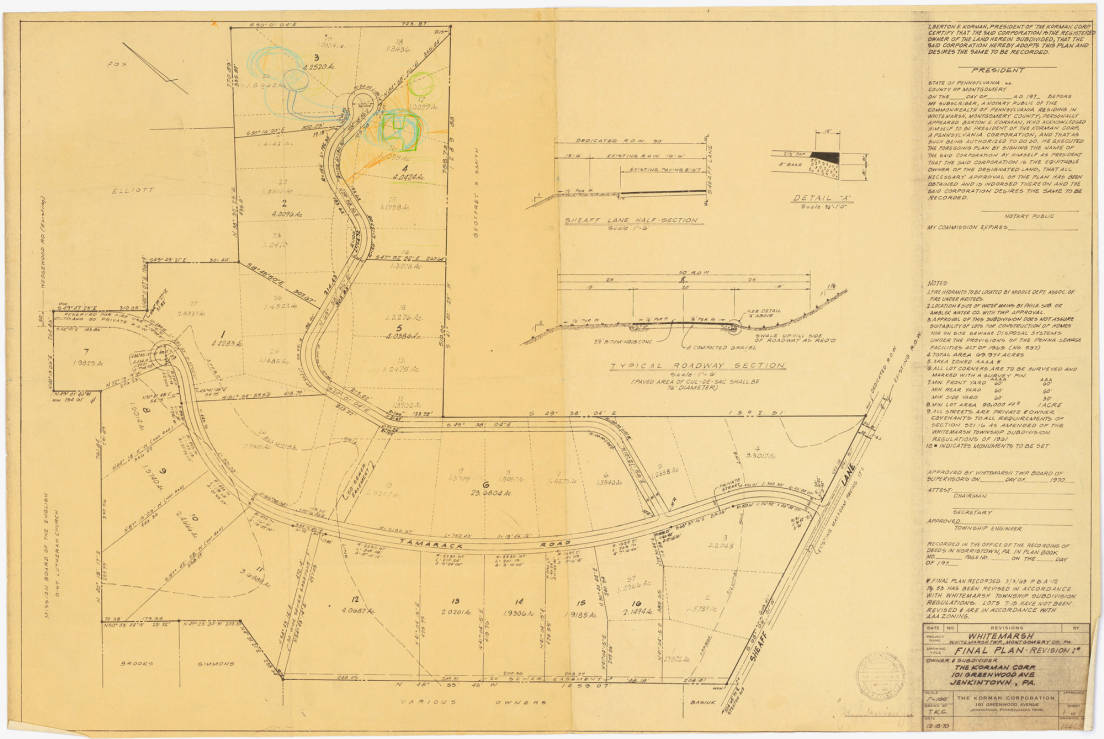

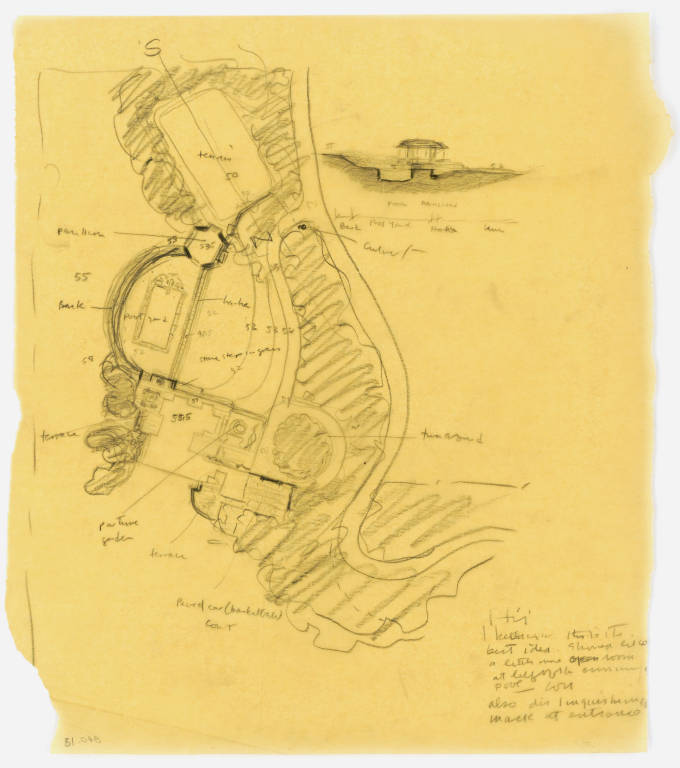

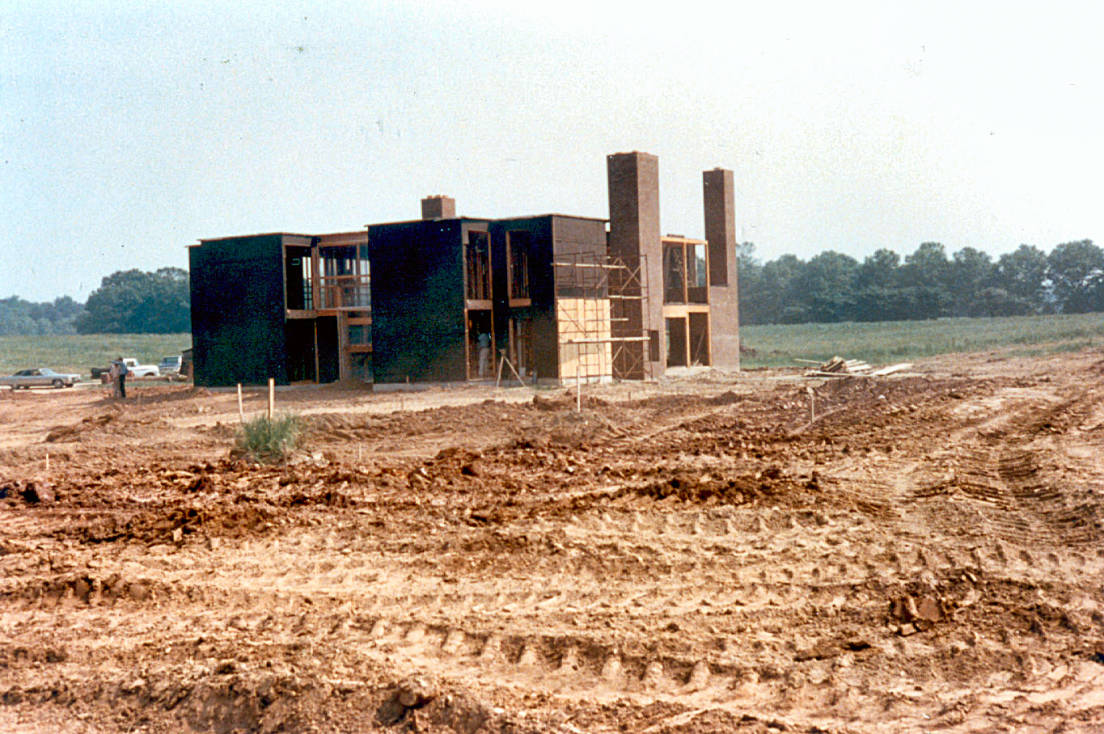

The blank canvas that Pattison discovered in 1971 at the Kormans’ also offered opportunities to think about procession and juxtaposition. Remembering her first view of the site, Pattison described it as “absolutely barren.” 2Interview with Harriet Pattison, July 2013. All subsequent quotations, unless otherwise cited, are from this conversation. The four acre lot was almost flat. The soil was every gardener’s nightmare: heavy clay. Together, she and Kahn worked to transform the land while still preserving traces of its rural heritage. For Kahn, she said, the site had little connection to 1970s suburbia. Instead, the commission offered a new way to explore architecture’s origins—the family dwelling—while simultaneously building for the future. “He realized that the earth was limited and that houses, no matter how grand… had to be modest, and not to take over the land.”

In her plans, Pattison used curves and slopes to create contrast between the land and the house’s geometry, a sense of drama and mystery. She created gentle undulations in the lawn, and drew upon a feature from British 17th and 18th century landscaping called a “ha-ha” to divide the swimming pool from the rest of the yard. The “ha-ha” is named for the surprise it produces: a dry trench forms a boundary between the estate’s gardens and grounds, constructed so that the lawn appears to extend seamlessly from the house to the horizon.

Pattison planted pine trees along the driveway and garage. Their branches delicately screen a visitor’s approach to the house and landscape: until you enter the living room, where the floor-to-ceiling windows reveal an open field, there is only a suggestion of what lies beyond the house.

She sought to create outdoor spaces (pool, tennis court, patio) that were like rooms themselves, drawing the family outdoors and creating a happy symmetry between domestic and natural realms. A brick patio, for instance, mirrors the brick floor that surrounds the living room inglenook. Originally, the brick extended along a path to the pool area (it was later replaced with bluestone, which is easier for swimmers’ wet feet to navigate).

Pattison believed that the Korman house is unique among Kahn’s residential works because of its potential to enrich the tradition of American country houses. She pointed out that American country homes can be modest in size, especially when compared to their British relatives, but modesty is supplemented by extraordinary setting and prospect. 3Pattison cited Philip Johnson’s Glass House and John Penn’s Solitude, in Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park, as examples of modest American country homes.

Continuity and self-containment are also key: the land is meant to be passed down through the generations, keeping families together in the same place. Kahn saw this too, she said: in his 70s, he was increasingly thinking about “how humans would dwell together as a community, and in harmony with the land.”

Landscaping updates were made in 1998 by Studio Intra Muros’ Joan Pierpoline in consultation with Anu Mathur, and again in 2005 by David Rubin in consultation with Laurie Olin. A new pool house complex, tennis court, entry sequence, and patios were added, along with a reflecting pool outside of the living room. The Kormans consulted with Pattison in 2013-14 to develop and refine the site further.